Six Honda Icons — and an Honourable Mention

Six defining motorcycles, one considered outlier — and how Honda reshaped expectations through use rather than spectacle.

Part I

Six Icons, and One Honourable Mention

There are machines that arrive with noise and promise, and others that reveal their importance only later. Among them some of Honda’s most influential motorcycles did both.

They generated excitement when they appeared — sometimes enormous excitement — and then, over time, they changed expectations so thoroughly that the excitement became less important than what followed.

Honda’s history is not a story of understatement at launch. The CB750 did not slip quietly into the world. It arrived in 1969 as a shock — fast, smooth, electric-started, and attainable in a way that forced everyone else to respond. Riders lined up. Competitors recalculated.

What matters, looking back, is what happened after the noise subsided.

Instead of aging into temperamental legends, Honda’s most consequential motorcycles settled into use. They didn’t demand adaptation. They didn’t punish mistakes.

They didn’t insist on being treated as special objects. Over time, they altered daily habits — how far people rode, how often they rode, and how much thought they gave to the machinery beneath them.

That shift didn’t happen all at once. It unfolded across decades, through machines that looked very different from one another but shared a common instinct: to make effort recede.

Years later, mechanics spoke about them the way gardeners talk about old tools — not because they were precious, but because they kept showing up. Riders noticed later. Writers noticed last.

This is not a story about first impressions.

It is a story about what remained.

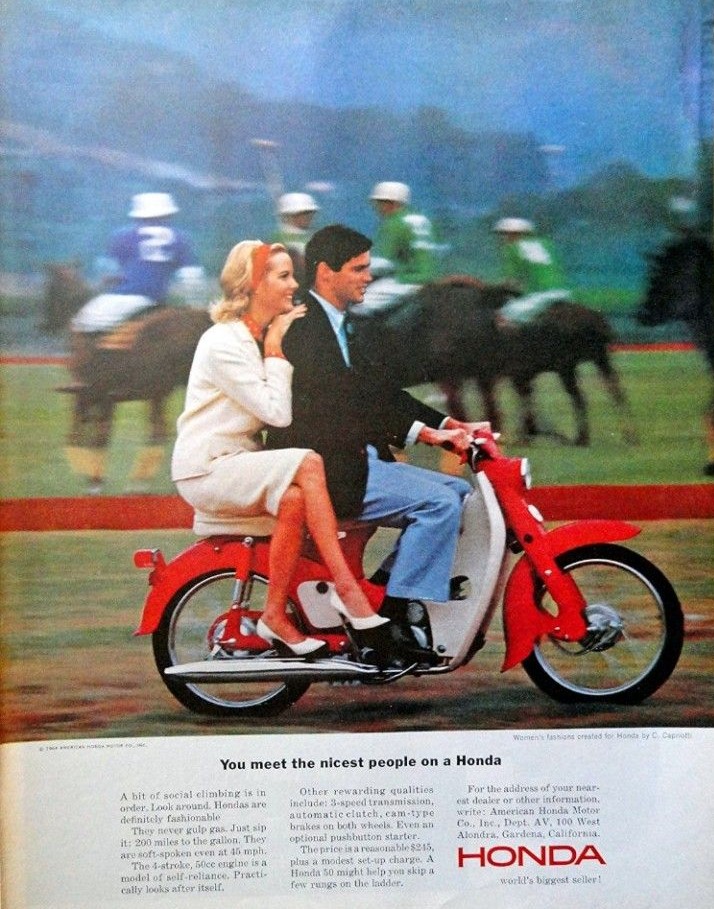

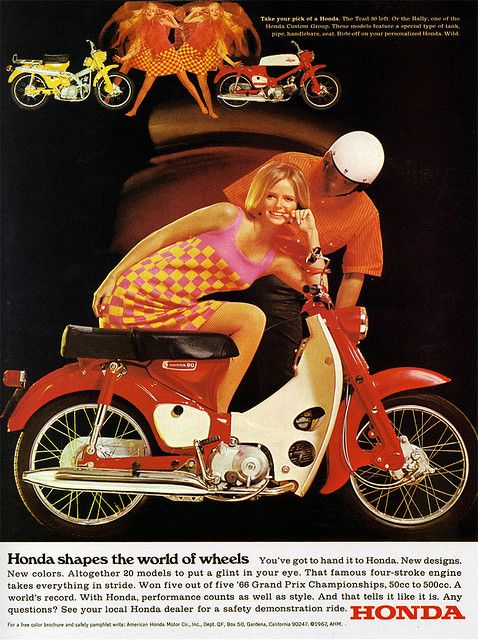

Honda Super Cub (1958–present)

The motorcycle that moved the world

The first Super Cub appeared in 1958, and nothing in Honda’s lineup — or anyone else’s — had prepared the world for it.

It was not faster than existing motorcycles, nor more powerful, nor more glamorous. In many ways, it barely announced itself at all. And yet, it would become the most consequential machine Honda ever built.

Not an evolution of an earlier model, it was conceived as a reset. At a time when motorcycles still carried the weight of mechanical obligation — kickstarts, oil leaks, noise, and a certain social posture — the Cub removed barriers rather than adding capability.

Step-through, leg-shielded, easy to start, and unintimidating, it offered something radical: permission. Permission to ride without preparation, without bravado, without explanation.

At modest speeds through town, the Super Cub reveals its intent. The engine hums rather than asserts itself.

The centrifugal clutch smooths away hesitation and error. Inputs feel advisory rather than imperative. Riding it feels less like operating a machine than joining a rhythm that already exists — traffic, errands, daily life.

Permission, engineered

That ease was no accident. Honda engineered the Cub around neglect as much as care. Low compression reduced stress. Generous tolerances assumed inconsistent maintenance. An enclosed drivetrain protected vital components from weather, dirt, and indifference.

The Cub expected to be left outside, started cold, ridden briefly or endlessly, and forgotten again. Over time, it earned the quiet affection usually reserved for old tools — not because it was cherished, but because it never failed to appear. Compression stayed. Wear was even. Nothing sulked.

When mobility became ordinary

What followed was something no marketing strategy could have orchestrated. The Cub spread quietly, continent by continent, until it became background. Farmers rode them. Shopkeepers rode them. Postal workers, students, families. In many places, the Super Cub ceased to register as a motorcycle at all and became infrastructure — a neutral presence in daily life.

More than one hundred million Super Cubs would be built, making it the most produced motor vehicle in history. But its importance is not found in numbers alone. The Cub did not just sell mobility; it normalized it. People rode in ordinary clothes. They rode every day. Riding stopped being an activity and became a habit.

Everything Honda would later do — racing, touring, performance — rests on this foundation. The CB750’s civility, the Gold Wing’s endurance, the Africa Twin’s tolerance for abuse all echo the same original assumption: that a motorcycle should work quietly, repeatedly, and without ceremony.

The Super Cub did not conquer the world.

It moved through it — one ordinary day at a time — and never left.

Honda CB750 Four (1969–1978)

The moment performance became ordinary

When Honda introduced the CB750 in 1969, it did not arrive as an experiment. It arrived as a statement — and one that landed with unusual force.

Four cylinders in line, an electric starter, a front disc brake, and a level of refinement that, until then, belonged either to racing motorcycles or to expensive, hand-built machines few riders ever encountered.

There had been no “regular” CB750 before it. The CB750 was the CB750 Four — a clean-sheet design that drew as much from Honda’s Grand Prix four-cylinder engines as from its growing confidence in building durable road machines at scale. It did not refine an existing category. It replaced one.

When speed stopped being an event

What startled riders most was not peak speed, but how little drama accompanied it. At sustained highway velocities, the engine did not strain or vibrate; it simply continued. Acceleration arrived smoothly, without mechanical urgency. Speed stopped feeling like an event and began to feel like a condition — something you entered and remained in, rather than achieved and escaped.

That behavior was the result of deliberate restraint. Conservative cam timing favored durability over theatrics. Generous oil capacity and robust cooling assumed sustained use rather than short bursts.

Electric start removed ritual and uncertainty. The disc brake repeated predictably rather than impressing once. The chassis favored stability over sharpness, trusting riders to discover its capability gradually.

What remained after the excitement faded

What ultimately mattered was not how long the model remained in production, but what it changed. Years later, high-mileage engines revealed even wear and few surprises. Nothing loosened inexplicably.

Nothing demanded constant correction. Riders noticed that long days no longer required planning around the machine. Distance expanded, not because the CB750 encouraged bravado, but because it removed reasons to stop.

Within Honda’s own lineage, the CB750 marks a pivot rather than a peak. It closed the era of temperamental performance and opened one where speed, smoothness, and longevity were expected to coexist.

When Honda ceased production of the SOHC CB750 in 1978, it did not signal an ending so much as a completion. The idea had already taken hold.

Once performance became smooth, reliable, and ordinary, there was no returning to what came before. Competitors could chase numbers, refine handling, or add complexity, but the baseline had shifted. Performance was no longer something a rider had to endure.

The excitement that greeted the CB750 eventually faded.

The expectation it created did not.

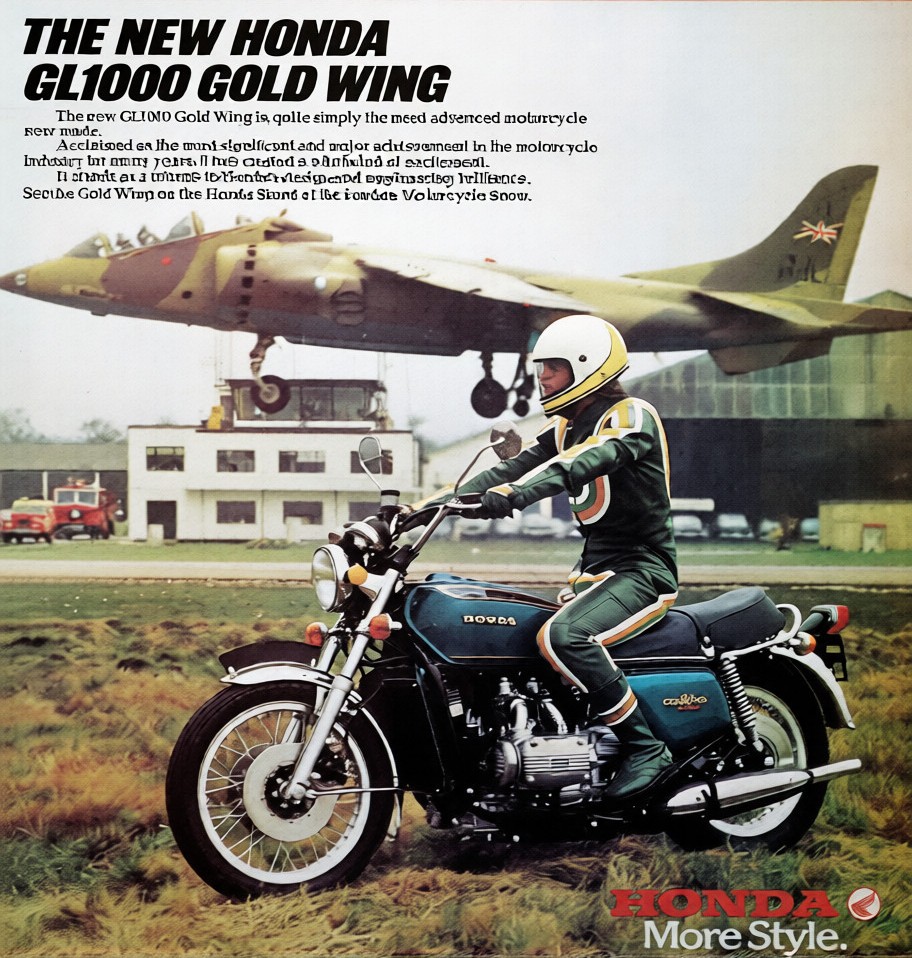

Honda Gold Wing GL1000 (1975)

When distance became effortless

The Gold Wing began, quite literally, as a misunderstanding.

When Honda introduced the GL1000 in 1975, few people knew what to make of it. It was large, but not ostentatious. Smooth, but not obviously luxurious.

It lacked the visual cues that, at the time, defined touring motorcycles. No fairing. No trunk. No promise of indulgence. What Honda had built was something quieter — and far more radical.

Coming six years after the CB750, the Gold Wing applied the same discipline to a different problem. Where the CB750 had normalized speed, the GL1000 set out to normalize distance.

At sustained highway speeds — eighty-five, ninety miles an hour — fully loaded and unhurried, the Gold Wing revealed its purpose. Wind pressure stabilized rather than fatigued. Vibration receded into the background. Heat remained controlled.

Distance stopped presenting itself as something to be conquered and became something to inhabit. Riding no longer felt like a series of efforts, but like a continuous state.

This was not achieved through padding or excess. Early Gold Wings relied almost entirely on mechanical calm. The flat-four engine carried its mass low and wide, stabilizing the chassis without stiffness.

Liquid cooling kept temperatures consistent regardless of speed or load. Shaft drive eliminated maintenance rituals that accumulated fatigue over long days. Comfort was not added piece by piece — it emerged as a consequence of balance.

Distance without negotiation

Over time, engines routinely surpassed 100,000 miles with little internal drama. Bearings wore evenly. Drivetrains stayed aligned. The weight of the machine, which on paper should have punished components, rarely did. The Gold Wing behaved as if it expected to be used continuously, and had been designed accordingly.

Over time, the Gold Wing would evolve into something more obviously luxurious. Fairings grew. Electronics multiplied. The model became synonymous with touring prestige. Yet the original GL1000 remains the clearest statement of intent — a motorcycle that treated endurance not as a challenge, but as a baseline condition.

In Honda’s lineage, the Gold Wing occupies a distinct place. It was not an outgrowth of touring culture, nor a response to competitors. It was a declaration that long-distance riding did not need to involve sacrifice, strain, or bravado. That distance, handled correctly, could simply feel normal.

The Gold Wing did not redefine touring by adding more.

It redefined it by asking less of the rider.

Honda CBR900RR FireBlade (1992)

When lightness became the real horsepower

By the early 1990s, the superbike category had begun to drift. Performance figures climbed steadily, but so did mass. Bigger frames, longer wheelbases, more cylinders, more bodywork — each new model promised speed while quietly demanding more effort in return. Power was rising, but accessibility was not.

Honda chose not to follow that trajectory.

When the CBR900RR FireBlade appeared in 1992, it didn’t present itself as a technological leap so much as a philosophical one. Instead of asking how much power a motorcycle could carry, Honda asked how little mass it needed to manage it.

The result was not a stripped-down machine, but a carefully concentrated one — physically smaller than its displacement suggested, and noticeably lighter than anything else in its class.

When mass mattered more than output

Weight was removed everywhere it could be spared. The wheelbase was shortened. Mass was centralized. The engine was narrowed. Geometry did the work that horsepower no longer needed to. Nothing about the FireBlade felt accidental, and nothing about it felt excessive.

On the road, that thinking translated immediately. Acceleration did not arrive with drama or strain; it simply accumulated. Riders often found themselves traveling far faster than intended, not because the bike felt wild, but because it felt so composed.

The FireBlade didn’t demand attention — it rewarded it. Steering was light without being nervous. Transitions were clean. The motorcycle felt legible, as though its responses were always a half-second ahead of conscious thought.

Control replacing intimidation

What made this approach so influential was not how fast the FireBlade was, but how usable that speed became. Control replaced intimidation. Confidence replaced calculation. Riders didn’t feel like passengers to the engine; they felt involved, even improved.

In Honda’s internal lineage, the FireBlade was not an escalation of the CB750’s logic or a continuation of race homologation thinking. It was a correction — a reminder that performance had drifted away from the human scale, and that bringing it back did not require less ambition, only different priorities.

Nearly every modern sportbike would eventually absorb this lesson, even as power figures climbed again. Weight reduction, mass centralization, compact packaging — these ideas became standard not because they were fashionable, but because the FireBlade demonstrated how profoundly they changed the riding experience.

The CBR900RR did not redefine speed.

It redefined how little effort speed needed to ask for.

Honda VFR750R RC30 (1987–1990)

Racing, without compromise

The RC30 was never meant to explain itself.

Introduced in 1987, it carried a V-four engine with gear-driven cams that come alive above 9,000 rpm, the sound tightening as the motorcycle reveals its purpose.

The RC30 was built so Honda could race — and win — in World Superbike, and it carried that purpose openly. Everything about it assumes intention. Nothing is softened. Nothing is added for reassurance.

Where earlier Hondas sought to make performance ordinary, the RC30 did the opposite. It insisted on precision. The V-four engine, with its gear-driven cams, does not wake up gently.

Below nine thousand rpm it behaves politely enough, but above that threshold it hardens, sharpens, and begins to demand commitment. The sound changes. The response tightens. You are reminded, unmistakably, that this machine was designed to live at speed.

A motorcycle built for the rulebook

On the road, the RC30 offers little in the way of accommodation. Heat rises. Noise persists. The riding position loads wrists and concentrates attention. Comfort is not absent by accident; it is absent by design. This is not transport. It is proximity to racing machinery.

That severity extended beneath the surface. Tolerances were tight and remained so. Valve timing did not drift. Components wore honestly rather than forgivingly.

Over time, an unusual clarity emerged: nothing felt compromised for longevity, yet nothing had been softened for convenience. The motorcycle behaved as though it expected correct maintenance — and rewarded it.

In Honda’s lineage, the RC30 sits apart. It is not a development of the CB750’s civility, nor a precursor to the FireBlade’s accessibility. It is an outlier — a moment when Honda allowed its racing discipline to reach the road with minimal translation.

Its production run was brief, ending in 1990, and it was never intended to be repeated. Later homologation models would follow, but none with the same clarity of purpose. The RC30 endures not because it tried to be loved, but because it never tried to be anything else.

It remains important precisely because it refused to generalize.

The RC30 did not stay by becoming ordinary.

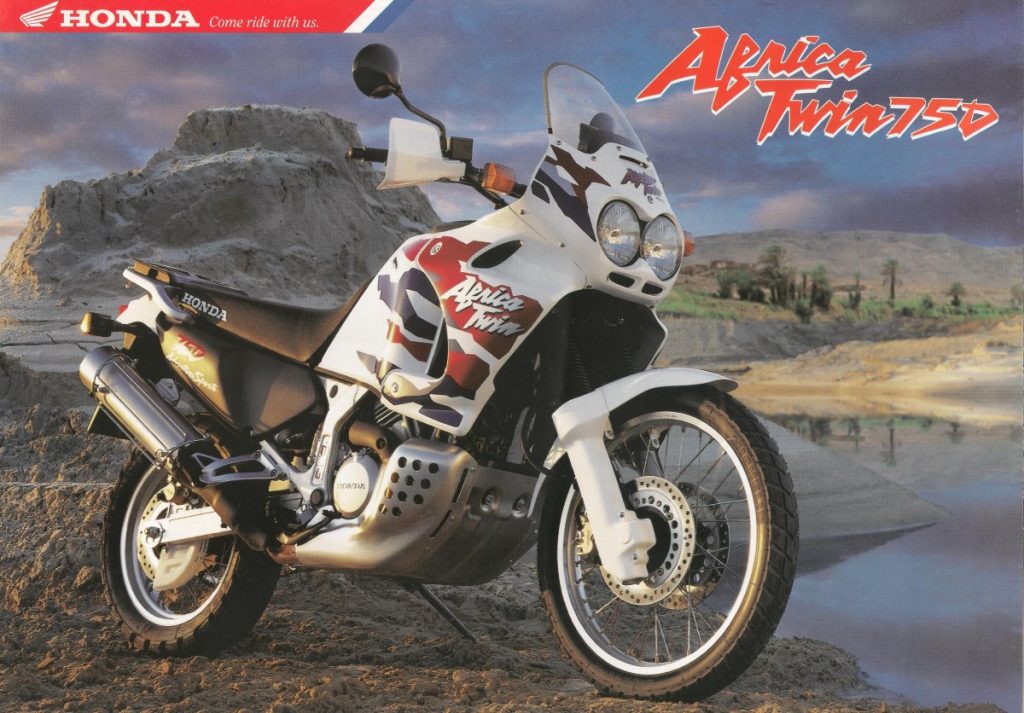

Honda Africa Twin

Adventure, made legitimate

(1988–2003; revived 2016–present)

The Africa Twin’s story is not continuous, and that matters.

When Honda introduced the first Africa Twin in 1988, it was not launching a lifestyle category or a brand exercise. The motorcycle emerged directly from Honda’s Dakar Rally experience, shaped by long days, mechanical attrition, and the realities of distance far from help. Its purpose was endurance, not escape.

That original lineage — the XRV650 followed by the XRV750 — ran until 2003. During that period, the Africa Twin earned its reputation not through spectacle, but through repetition. It assumed weight, heat, poor fuel, and uncertain maintenance. That design was intended to continue where other machines hesitated, and to do so without dramatizing the effort.

Endurance learned the hard way

On the road, and especially beyond it, the Africa Twin revealed a particular kind of calm. At moderate speeds, fully loaded, it did not feel eager so much as settled.

Suspension favored stability over sharp response. Torque arrived early and remained useful. Cooling capacity assumed sustained load rather than brief exertion. Progress felt steady, unremarkable — and that was precisely the point.

What distinguished the Africa Twin was not where it could go, but how little it protested along the way.

Broken pavement, corrugation, dust, and heat were absorbed rather than amplified. Riders crossed borders quietly. Return journeys felt assumed rather than hoped for.

In workshops far from where the bikes were sold, mechanics saw the same thing repeated: fatigue resisted, failures arrived honestly, and wear accumulated evenly. When things failed, they did so honestly. The motorcycle behaved as if it expected to be depended upon.

When Honda discontinued the Africa Twin in 2003, it did not replace it directly. The name disappeared for more than a decade. That absence mattered, because it separated reputation from continuity. The Africa Twin became something remembered rather than maintained.

Credibility earned through repetition

Its return in 2016 was not an act of nostalgia. Honda revived the name because the original machines had established a credibility that could be carried forward.

The modern Africa Twin is different in form and technology, but the intent remains legible: a large motorcycle designed to tolerate distance, uncertainty, and repeated use without demanding heroics.

Within Honda’s history, the Africa Twin occupies a rare position. It represents competition knowledge translated back into everyday durability, and then rediscovered years later because the lesson had not expired.

The Africa Twin did not invent adventure riding.

It made it credible — first through use, and later through memory.

Honda Transalp

Honourable Mention (1987–2012; revived 2023–present)

The Transalp’s story is quieter than most — and that, in many ways, explains it.

When Honda introduced the Transalp in 1987, it was not responding to a category so much as acknowledging a gap.

It was positioned deliberately between road-focused CB models and the rally-derived ambition that would soon become the Africa Twin, intended for riders who moved between surfaces, distances, and expectations without seeking extremes.

It arrived a year before the Africa Twin, and the distinction between the two was intentional. Where the Africa Twin leaned toward resilience under load, the Transalp favored balance.

Less tall, less heavy, less demanding — not as a compromise, but as a considered alternative. It assumed mixed roads, ordinary speeds, and repeated use rather than singular journeys.

How it behaves on ordinary roads

On the road, that intent is immediately legible. At steady pace on imperfect surfaces, the Transalp feels composed without feeling inert. Weight is manageable. Steering remains light. Transitions require little correction. The motorcycle does not insist on attention, nor does it withdraw from it. It simply responds.

That character was shaped by restraint rather than ambition. Power delivery favored torque where it was actually used. Suspension was tuned for real roads rather than imagined terrain. Ergonomics encouraged familiarity over theater. Nothing needed to be endured before being enjoyed.

The pattern revealed itself quietly over time.. Transalps arrived for service, not rescue. Engines ran at modest stress. Components wore predictably. Parts sharing across Honda’s range simplified maintenance and extended working life. They aged evenly, without drama, and without asking to be preserved as objects.

The original Transalp line ran, in various forms, until 2012. When it disappeared, it did so quietly — not because it had failed, but because it had never depended on attention in the first place. Its absence, like the Africa Twin’s, created space for reflection.

When Honda revived the Transalp name decades later, it did so not to resurrect a myth, but to re-engage a set of priorities that had proven durable: balance over excess, usability over spectacle, continuity over escalation.

Balance as a deliberate choice

Within Honda’s history, the Transalp occupies an unusual position. It is not an icon in the traditional sense, nor a benchmark others were forced to follow. Instead, it stands as a reminder that relevance does not always announce itself loudly, and that some motorcycles matter precisely because they resist being reduced to statements.

We include the Transalp here not as a defining moment, but as a clarifying one — a motorcycle that shows how often Honda understood the middle ground before anyone thought to name it.

Taken together, these motorcycles were not competing answers to the same question. They were successive reductions of effort — fewer demands, fewer corrections, fewer compromises.

Each one made something previously difficult feel normal, and once normal, permanent. The noise that greeted them at launch mattered far less than the silence that followed, when riders stopped talking about the machines altogether and simply kept going.

Part II

Why These Machines Became Reference Points

Taken together, these motorcycles were not competing answers to the same question. They were responses to different moments, different pressures, and different understandings of what riders needed at the time. What links them is not category or performance, but a particular relationship with use.

Expectation, not escalation

Each of these machines reduced something. Effort. Attention. Compensation. They made activities that had once required planning, endurance, or mechanical sympathy feel increasingly ordinary.

Speed without strain. Distance without fatigue. Reliability without ceremony. In doing so, they shifted expectations rather than merely satisfying them. That shift is easy to miss at first. It reveals itself later, beyond what spec sheets can capture.

Wear patterns tell stories long before nostalgia arrives — engines that do not grow temperamental, fasteners that do not loosen inexplicably, frames that age evenly rather than dramatically. Nothing heroic. Nothing fragile.

Riders notice it more slowly. A sense that days stretch longer. That routes extend without calculation. That attention drifts away from the motorcycle and back to the road, the weather, the light. The machine stops insisting on itself.

Not all of these motorcycles occupied the same role in Honda’s history. Some remained in production for decades, evolving carefully. Others appeared briefly and disappeared just as deliberately, leaving behind ideas so complete they no longer required repetition.

The CB750 belongs to that latter group. Its production run ended, but its logic did not. Once performance became smooth, reliable, and ordinary, there was no returning to what came before.

That distinction matters, because it clarifies what Honda understood better than most: historical significance is not the same as longevity. A machine can matter profoundly without persisting unchanged, just as it can persist without continuing to matter.

- The Gold Wing became a reference point by redefining distance as a condition rather than a challenge.

- The Africa Twin earned its place by demonstrating trust far from assistance.

- The FireBlade reframed performance around control instead of escalation.

- The RC30 stands apart as a moment of absolute clarity — racing discipline briefly allowed onto the road.

- The Super Cub reshaped daily life by removing intimidation altogether.

And the Transalp reminds us that some motorcycles matter not because they dominate conversation, but because they continue to make sense long after categories have shifted around them.

What use reveals over time

Honda’s most important contribution may not be any single model, but the expectation these machines collectively established: that motorcycles could be used hard, lived with casually, and trusted without constant negotiation.

Some became icons.

Others became reference points.

Each form of significance is real — and both continue to shape how motorcycles are designed, ridden, and understood.

This article reflects editorial opinion based on historical context and published road tests.